have we reached the end of influencing?

de-influencers and marketing "scandals" are exposing the bullshit of it all.

Something fantastic is happening on TikTok — the de-influencers are here.

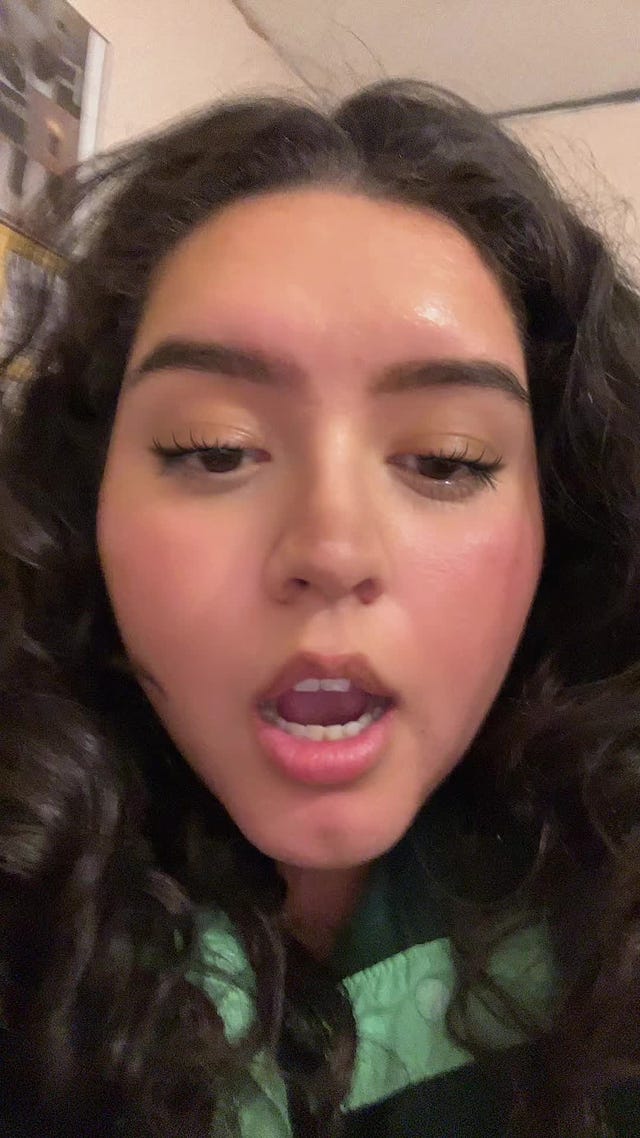

The trend seems to have originated in early January, but I first saw a de-influencer video on my for you page on Monday by user sadgrlswag. In a simple video of her face, she says, “I am here to deinfluence you. Do not get the Ugg minis, do not get the Dyson Air Wrap.” She continues on, listing off trendy things like the Stanley cup and Colleen Hoover books, wrapping it up with a friendly “If you do any of those things, a bomb is gonna explode.” It’s perfect.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

People are using her original sound on their own videos, and others are making videos of their own. Some of them are framed differently, with people saying, “here are the products I was influenced to buy that I didn’t like.” Some of them are similar in format but have people making their own lists: Bloom greens, On running shoes, Charlotte Tilbury Flawless Filter.

These videos are saying the quiet part out loud — that the only reason we’re buying these things is because we’re being told to do so. Not because of their quality, their function, or how they look. They’re being outed simply as trends that have taken over because of social media.

Does this signal that we’re starting to lose trust in influencers?

Despite it clogging our social media feeds for the last few years, influencer marketing isn’t a necessarily new phenomenon. In fact, word-of-mouth marketing dates back centuries. But as we know it now, influencer marketing started out with pre-social media mommy bloggers, then truly came into its own on Instagram. Reports say that in 2022, influencer marketing was a $16.4 billion industry.

None of us are safe from being influenced, no matter how much we try not to be. I bought Barkeeper’s Friend cleaner because two of my favorite food TikTokers recommended it. I bought The Ordinary’s squalene cleanser because I saw it on an Instagram story. Influencers have even influenced my behavior — I’m now a proponent of the “Sunday reset.” And on that note, would you really be eating oysters and tinned fish if they weren’t trendy? Think hard about that one.

But it seems like we’re becoming increasingly more aware of the facade and have started calling it out. In addition to the de-influencers, there’s one recent influencer marketing flop in particular that’s showcasing the flaws and disingenuous nature of influencer marketing. The reactions to it are proving how our views on influencers have changed.

On January 25, TikTok user mikaylanogueira posted a video touting the incredible lash-lengthening capability of the L’Oreal Telescopic Lift mascara. She puts it on, and the video cuts back — her lashes look unreal. Literally! Thousands of comments say they recognize the Ardell false lashes they think she added on at the end, and videos show the inconsistencies between the real mascara application and the purported end result. It’s one of the most blatant examples in recent memory of an influencer lying about the quality of a product.

And now, it seems like influencers themselves are being especially up-front about the facade. In a seemingly now-deleted video, TikTok user mads.yo responds to the Mikayla scandal, saying, “It might be false advertising, but isn’t everything kind of false advertising?” User madeleine.white posted another video sharing all the ways her features have been exaggerated in ad campaigns as a model, from hair extensions to stuffed bras. She points out that advertisers have been doing this forever and exaggerating how well a product works is nothing new.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

But to me, the point of influencer marketing is that viewers are getting what they assume is a “real” and “honest” review from someone they trust. Whether that’s misguided or not, we can talk about another time. But the point of influencer marketing seems to be a lack of flash and glamour that is juxtaposed by typical advertisements which often contain obvious exaggerations. People are more likely to believe someone who is “honest” and “real” on social media than a TV ad featuring an unknown actor. But if influencers are exaggerating the quality of a product too, how are they any different from other forms of advertising?

This is part of why de-influencing as a trend is encouraging to me — influencer marketing has likely always been a facade but was pitched as something more trustworthy than traditional marketing. But it’s nothing new, and people are pointing it out.

I’m happy to see the impending downfall of influencers because the rise of influencing has created a sad harmony of similarities among us all. From videos of classrooms littered with Stanley cups to TikToks showcasing acrylic shelves and coffee tables, internet users — the influenced — have succumbed to an eerie sameness. Kyle Chayka, an author and New Yorker writer, talked about this in a 2016 article for The Verge called “The Subway That Sunk: How Silicon Valley helps spread the same sterile aesthetic across the world.”

In his article, Chayka points out the similarities between spaces — specifically coffee shops. Wooden tables, Edison bulbs, white walls, a place that is perfect for opening up your laptop, throwing in your Airpods, and grinding.

“It’s not that these generic cafes are part of global chains like Starbucks or Costa Coffee, with designs that spring from the same corporate cookie cutter. Rather, they have all independently decided to adopt the same faux-artisanal aesthetic. Digital platforms like Foursquare are producing ‘a harmonization of tastes’ across the world, Schwarzmann says. "‘It creates you going to the same place all over again.’”

This is happening with more than the places we travel; it’s happening in our homes and our closets and our medicine cabinets as we relentlessly purchase the products that influencers promise have changed their lives. As we continue consuming, our lives start to blend together and look the same. We all have the same hair products, the same greens, the same shoes. It reminds me of when the rich girls in my eighth grade class would all go in on a Brandy Melville order and all end up having the exact same clothes.

That’s why it’s thrilling to have people calling out the bullshit of influencer marketing. And putting it in plain terms — “You don’t need this.” It’s a simple thing that reverses the claims of every content creator, and has started rewiring my brain too. Now seeing things that I think I like is followed by an immediate interrogation: Do I need that, or am I just succumbing to the messaging? Plus, if I get them, apparently a bomb will explode.